The Interior Design of the Jurassic Park Visitors’ Center Foreshadows the Plot

In a recent post about Jurassic Park (1993), I argued that the design of the visitors’ center as metatext supports the thesis of the overall film as a text. This week, I want to talk about how the design of the interior of the building does the same.

“But Hype, don’t you think that maybe, just maybe, this time, The Curtains Are Just Blue?” Nope.

And even if they are, I ain’t gonna pay that no nevermind, because art means something and even if I’m reading something into the set design that the artists didn’t intend, I still think it’s worth talking about.

* * * * *

As I covered in depth in my previous post, the interior of the visitors’ center is post-modern, which is a style that integrates function and symbolism. The function of the visitors’ center is to provide a place to welcome patrons of Jurassic Park and introduce them to—as Hammond says—“living biological attractions so astounding that they’ll capture the imagination of the entire planet.” Symbolically, the building represents a temple celebrating the scientific innovation that has elevated man to a god that can render nature obsolete.

The architectural semiotics providing this symbolism borrow from various historical influences, but with the number of architectural characteristics on display, we could be here for days talking about them all. I’ll spare us by focusing on the two most prominent influences—and the two I personally care for the most. Listen, it’s my blog. If you want a fair and balanced treatment of architecture, I’m not your gal. But if you want to check out the ramblings of a woman who has been obsessed with the ancient world and brutalism since her childhood, read on.

The two architectural styles I want to focus on are: (1) the classical design elements reminiscent of grandiose places of worship and (2) the brutalist elements we associate with the Information Age. The classical elements evoke gravitas and majesty, while the brutalist ones communicate innovation, monumentality, and permanence.

Classical Design Elements

Classical architecture is the style that originated in the Greco-Roman Mediterranean. There are two elements of classical architecture in the visitors’ center that really stood out to me because they are common in ancient temples: (1) a tholos and (2) a naos.

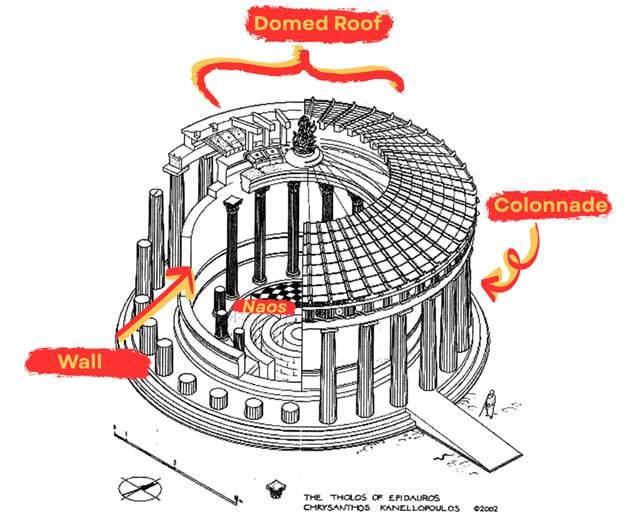

A tholos is a type of circular building with a domed roof, a circular colonnade, and a segregated space within the columns known as the naos.

The naos was the dwelling of the god and typically housed an idol, usually a statue representing a specific deity. Worshippers tended to commission the figure in a flattering pose and made from high-quality materials as a sign of respect—in part because it was believed that during a manifestation of the divine presence, the deity would either inhabit or visit their statue. It wouldn’t do to offend the god with a mediocre representation. Followers also demonstrated reverence by offering sacrifices with the hopes of coaxing the deity into manifesting themselves and altering the course of the followers’ lives. Icons were effectively the receptacle of the god—any disrespect to the icon was a slight to the god themselves. For these reasons, iconoclasm, idol theft, vandalism, and displaying stolen idols in humiliating conditions were common in the ancient world as means of subjugating political and religious enemies.

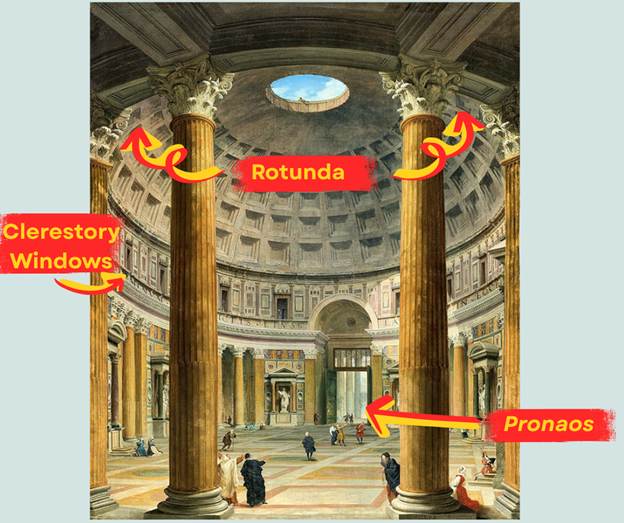

Eventually, construction materials got better and, well, architects engaged in that age-old tradition of trying to one-up each other, which spurred architectural innovations and buildings with greater structural complexity. With these changes, the design of the tholos began to vary as well, with architects adding antechambers (pronaos), fully enclosing the tholos in a walled structure (rotunda), and adding clerestory windows immediately below the domed ceiling. The most famous architectural example with all three of these features is the Roman Pantheon.

* * * * *

As an aside, the Pantheon is an incredible feat of engineering. No, seriously, after you finish this newsletter, go read up about it. I get chills every time I think about how people without calculators or Google (when it was still functional) could build majestic structures that are still standing today. And then I think about the Library of Alexandria, which is not standing because Julius Caesar was the fucking worst. And then I get sad thinking about all the people and cultures humans have destroyed in their quest for fortune and glory and conquest, by which point I have to blast music and dance around a bit because otherwise I’ll start thinking about every example of wholesale destruction my brain can conjure and I won’t be able to get out of bed. Then I donate to a few GoFundMes for people living through that shit right the fuck now and call my Congresscritters about it and get frustrated by how little I feel I can do. Then I go back to planning my little newsletter in the hopes that it will bring me some joy and bring someone else some joy too so we can keep getting out of bed and trying to do what we can, where we can, when we can.

* * * * *

Anyway, the Pantheon. It’s got a pronaos, a rotunda, and clerestory windows.

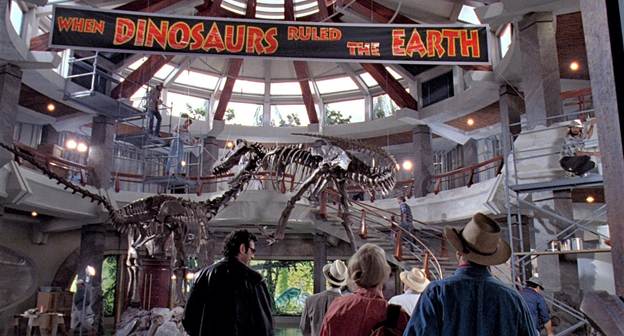

These features are also present in the atrium of the Jurassic Park visitors’ center. Can you spot them?

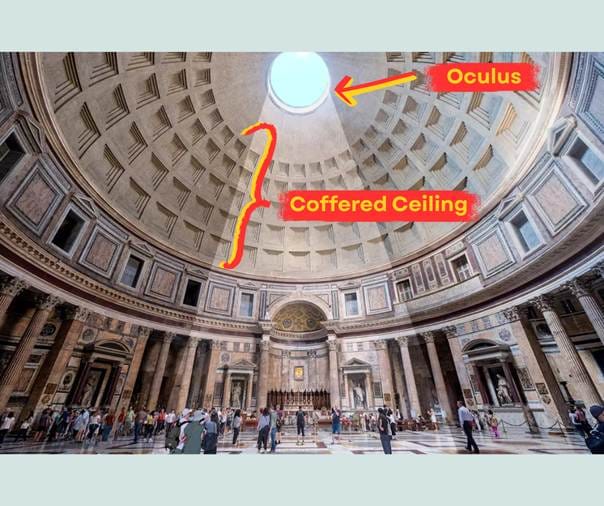

There are also a few details suggesting that an ancient building similar to the Pantheon inspired the design: both structures feature a coffered ceiling, which is roughly divided into concentric rectangles that decrease in size as they approach the oculus of the rotunda. In the Pantheon, the coffered ceiling is unreinforced concrete, while in the Jurassic Park visitors’ center, the coffers are windows set in steel supports.

In the words of Jim Trotter III, they are EYE-dentical!

Here’s where my brain started cooking up my lil theory about visual metaphors and foreshadowing, which came together when I peeped the brutalism.

Brutalist Design Elements

Brutalism is a post-war style characterized by imposing, functional designs that emphasize innovation and the solidity of the structure.

In the atrium, the steps and mezzanine are concrete, suggestive of fortification, while the railings feature sleek, red steel—a contemporary material representing a revolution in construction materials. Both elements communicate newness. Both elements also communicate permanence.

The atrium is a visual declaration that, through innovation, man is here to play god and make nature ancient history. The “When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth” banner is there to put a fine point on it.

Putting It All Together

As was the case with the exterior of the building, there is a semiotic mismatch between what the overall design intends to communicate and what it actually communicates.

Earlier, I mentioned that the naos traditionally housed the idol, which represents the god to whom the temple was dedicated. I also mentioned that followers took care to render the icon in a form befitting reverence, choosing high-quality materials and a portrayal that evoked the deity’s powers.

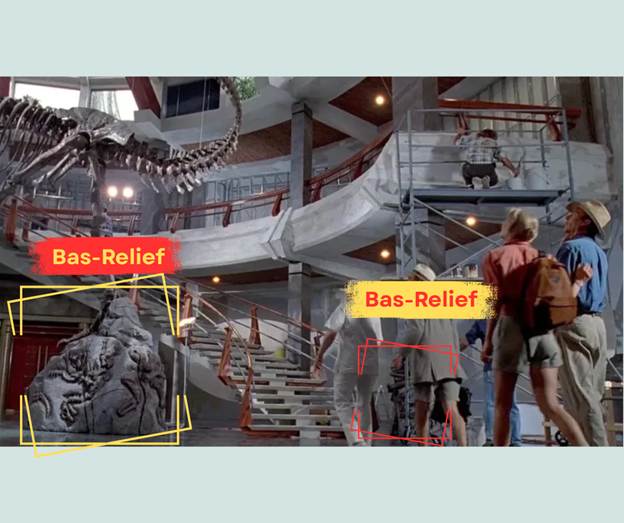

In the naos, we have a museum-quality T-Rex skeleton suspended on cables, posed as if it is fighting a sauropod. One leg rests on a concrete plinth. The plinth, like the base of each column surrounding the naos, continues this theme with an interesting detail: bas-reliefs mimicking fossils.

Rather than commissioning a sculpture based on flesh and blood dinosaurs, Hammond selected imagery that evokes extinction and obsolescence.

On the one hand, the T-Rex skeleton is exalted in the room—it towers above any other element. On the other hand, the use of (literally) degraded materials is lowering. It disrespects the tyrant king of the dinosaurs. It’s an intentional desecration of a great power.

::breaks the fourth wall to look directly into the camera::

Pretty rude, if you ask me.

But wait, there's more!

This also perfectly foreshadows the end of the film.

Remember, before, when I said that worshippers would leave sacrifices to coax a divine manifestation? And that a god might either embody its statue or visit it?

Grant and Ellie dedicated their lives to studying and understanding dinosaurs. And despite being enthralled by the rivals to fossilized dinosaurs, Grant and Ellie never fully apostasized from believing in the supremacy of the natural world. Rather, they reminded Hammond that the awe-inspiring scientific innovations at Jurassic Park were no match for nature itself.

“These are aggressive living things that have no idea what century they're in and they'll defend themselves. Violently, if necessary.” – Ellie

“I don't want to jump to any conclusions, but look, dinosaurs and man, two species separated by 65 million years of evolution have just been suddenly thrown back into the mix together. How can we possibly have the slightest idea what to expect?” – Grant

When Grant, Ellie, and the kids are cornered by the velociraptors, they (unintentionally) lure the raptors into the naos and—BAM!—they’re saved by one helluva Deus Ex Machina: an actual, factual T-Rex appearing near its physical representation. The Dino [R]ex Machina manifests—not as an inert relic, but as an aggressive living thing. (I will not apologize for the pun!)

In a decisive stroke of iconoclasm, the T-Rex destroys the ironically fragile facsimile by flinging one of the velociraptors into the skeleton, which also wrecks the interior of Hammond’s temple to a supposedly god-like humanity. This havoc parallels the ruin of Jurassic Park itself.

In an attempt to usurp nature, Hammond unwittingly reaffirmed its primacy. And if that ain’t the metatext meeting the moral of the story, I don’t know what is.

I love a good dramatic irony, don’t you?