In my quest to watch classic blockbusters I’ve either never seen or have largely forgotten, in July I watched Jaws, Alien, and Jurassic Park in quick succession, unintentionally programming myself a triple creature feature in which the creatures are not the true villains. Rather than subject y’all to the half-baked, bordering on unhinged, TED talk in my head about how all three movies offer a biting (ha!) critique of late-stage capitalism, today I’m going to keep to a thesis that’s been stalking me since I harpooned it with three barrels.

Three barrels. Three acts. Three types of villains.

The thesis? Forget the shark, the real monster of Jaws is people.

Today’s newsletter is about the villains of the first act: the people in positions of public trust.

* * *

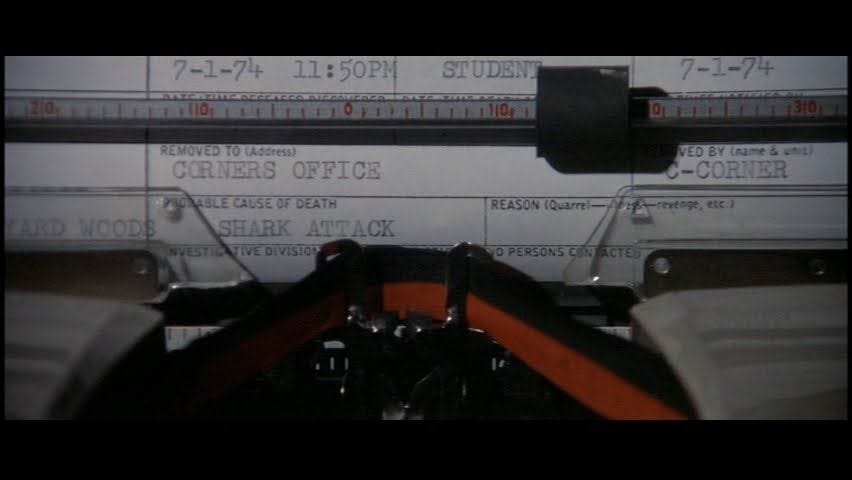

In Act One, Sheriff Brody is called to the beach to investigate some remains. Following this investigation, he goes back to his office where he fills out a form attributing the cause of death to a shark attack, based on the coroner’s examination. Immediately thereafter, Brody sets out to close down the beach to keep the residents and visitors safe. On his way to do so, a group of three men intercepts him with the aim of talking him out of this course of action. Here’s how that conversation goes:

Mayor Vaughn: You're gonna shut down the beaches on your own authority?

Sheriff Brody: What other authority do I need?

Meadows (editor of the local paper): Technically you need a civic ordinance or a resolution by the board—

Mayor Vaughn: That's just going by the book. We're really a little anxious that you're rushing into something serious here. This is your first summer, you know.

Brody: What does that mean?

Mayor Vaughn: I'm only trying to say that Amity is a summer town. We need summer dollars. And if the people can't swim here, they'll be glad to swim at the beaches of Cape Cod, the Hamptons, Long Island.

Brody: That doesn't mean we serve them up as smorgasbord.

Meadows: But we've never had that kind of trouble in these waters.

Brody: Well, what else could've done that to that girl?

Mayor Vaughn, turning to the coroner: A boat propeller?

Coroner, remembering his cue: Well, I think possibly, uh, yes, a boating accident.

Brody: That's not what you told me over the phone.

Coroner: I was wrong. We'll have to amend our reports.

Brody: And you'll stand by that?

Coroner: I'll stand by that.

While Mayor Vaughn presses his suit, the coroner walks away: Martin, a summer girl goes swimming, swims out a little far. She tires, a fishing boat comes along—

Meadows: It’s happened before.

Mayor Vaughn: I don’t think you appreciate the gut reaction people have to these things.

Brody: Larry, I appreciate it, I’m just reacting to what I was told.

Mayor Vaughn: Martin, it’s all psychological. You yell, “Barracuda,” everyone says, “Huh? What?” You yell, “Shark!” . . . we’ve got a panic on our hands on the Fourth of July.

This little crew, which I’ve dubbed the Brooks Brothers Brigade, for reasons that will be self-evident, are the film’s first villains. Their crimes are legion. In no particular order:

Crimes Against Fashion

Falsifying Official Records

Social Murder

At this point, you’re probably wondering what section of the Amity Island penal code I’m working from. It’s my own code because I *am* the law, okay? Don’t worry about it.

* * *

Count the First: Crimes Against Fashion

Upon information and bel—you know what? Let’s get right to the exhibit. You see this photo? Do you see what they’re wearing?

I know what you’re going to say. “Hype, don’t you think you’re letting your perception of these people be colored by your decade of living, working, and cocktail partying with people who unironically made shopping at Brooks Brothers their whole personality? Are you perhaps harboring prejudice against the people who walked so the J6ers could run? Is it possible you have unexamined trauma from running the gauntlet that is ivy league education, corporate law, and being forced to use your meager talents to advance the interests of people who don’t even know you’re alive instead of doing something noble because you are drowning in student loan debt?”

Sure. I’m a big girl. I have no problem admitting that I have some psychological damage from fighting for a seat at a table I was meant to flip.

So what? That doesn’t change the truth, which is that Mayor Vaughn, the guy in the anchor print jacket, is a tacky Outfit Repeater. And, as we know from Kate Sanders, this is basically a crime. Seriously, this man wears the anchor-embroidered jacket at least three times in just as many days. (You can’t fault me for being an Outfit Rememberer because the movie is only two hours long.)

It feels a little like Vaughn is wearing a costume that anticipates tourists’ ideas of what the mayor of a small, northeast coastal town should look like, which makes him one of those political “leaders” who is more interested in doing whatever will appeal to a hypothetical median person than actually leading. Here, the hypothetical median person isn’t even a member of his own community, but rather a visitor who may or may not spend money in the town to provide coveted economic stimulus. The man’s clothing is a walking, talking advert for using flashy trappings to distract from a lack of substance.

As for the coroner and the editor of the local newspaper, well, what can I say about the uninspired sartorial choices of those whose greatest ambition is proximity to power (other than that their tailoring is impeccable).

Count the Second: Falsifying Official Records

Even if I cannot criticize the gorge, lapel, and collar ratio on the coroner’s suit, because it is perfect dammit, he is guilty of falsifying evidence. After reviewing poor Chrissie Watkins’ remains, he unequivocally attributes cause of death to a shark attack.

But on the ferry, he backpedals, saying a boat propeller could have caused her death and that the official report will need to be amended. It is obvious from the exchange that the revision will be made to reflect a conclusion that is motivated by politics, rather than evidence. Because the coroner provides cover to keep the beaches open, Alex Kintner and that adorable dog both die.

Count the Third: Social Murder

The most surprising part of Jaws for me was how prescient it would be regarding the declining integrity and independence of the Fourth Estate. Meadows, the editor of the local paper, is part of the group trying to talk the sheriff out of keeping beachgoers safe, rather than doing what one might reasonably expect from a journalist, which would be to report on the scandal of the mayor and the M.E. pressuring the sheriff to change the official report and abandon action that would save lives.

The media can influence the public’s perception of reality. Its choice not to report a story is as significant as how it chooses to report a story. By choosing not to report on the shark attack, Meadows sided with business interests over the health and safety of the beachgoers. By doing so, by hiding the truth, Meadows was complicit in social murder.

What is “social murder”? It is a type of homicide that results from the collective actions of those who control the political system rather than from the act of an individual—namely, the premature death of the working class from the premeditated exploitation of capitalists. In many cases, social murder is the result of deliberate omission, rather than commission: refusing to provide workers with safety equipment, cutting corners in constructing residential buildings, refusing to fund socialized healthcare, practicing austerity politics, foregoing non-pharmaceutical interventions that would keep people safe in the Covid pandemic, etc. If this reminds you of necropolitics, you’re spot on. Necropolitics describes the system, while social murder is one of its outcomes.

In the case of Amity Island, the mayor refused to close the beach because it would be bad for short-term profits, which resulted in the social murder of Alex Kintner (and later the man in the canoe). While the film ensures the audience has disdain for Mayor Vaughn’s decisions and Brody gets a reality check when Mrs. Kintner slaps him for his part in her son’s death, the movie spends barely any time reminding the audience that the editor of the newspaper and the coroner were complicit in these deaths.

But any of these men could have decided to act instead of upholding the status quo. Any of these men could have opted for setting an example instead of following the path most profitable. And as the mayor, Vaughn is the obvious choice for exercising even one iota of leadership by shutting the beaches down until the islanders can weigh in. Yes, weigh in! That’s how low the bar is—remember what he and Meadows told Brody: to shut the beaches down “by the book,” one needs either a civic ordinance or a resolution by the town board. Both of these options require that the public be informed. Yet Vaughn decides to quietly do what will least offend the interests of the business class on Amity Island, instead of exercising the moral courage to offer the larger community the information that could keep them safe. He’s nothing but an empty (anchor-print) suit.

* * *

Let’s divide the opposite by the adjacent because, baby, it is time for a tangent.

“Monster” derives from the Latin monstrum, which itself derives from the Proto-Italic moneō, which means to warn, foretell, remind, or instruct. The cautionary aspect of monstrosity in “western” culture has long roots—the ancient Greeks and Romans regarded monsters as signs of divine wrath. This superstition resulted in extreme prejudice against disabled people in the Greco-Roman world, especially those with conditions that were considered “deformities.” Unfortunately, this prejudice remains right up until the present day and has informed certain mainstays of the eugenics movement, such as physiognomy, Ugly Laws, sterilization, and euthanasia—all of which rightwing politicians and governments are reviving across the global north.

Inextricably twined with this physical prejudice is a belief pervading “western” philosophy, science, and literature, tracing back at least as far as Seneca the Younger, that treats the external characteristics of those deemed “monstrous” as a reflection of their inner nature and morality. In short, disabled people and other out groups selected based on physical appearance look the way they do because they are sinful, wicked, or inadequately pious. I wasn’t able to determine when these fields evolved to regarding monstrosity as something that could be intrinsic yet have no external indicators, but I have a pet theory that it was around the time phrenology began to fall out of favor in the late 19th century, which by no coincidence is when Oscar Wilde published The Picture of Dorian Gray.

I believe that horror, as a genre, is uniquely situated to explore an internal monstrosity that is not betrayed by exterior aesthetics. While I’m not now—nor have I ever been—a fan of horror (because I scare easily), as a child, I had a fascination with early monster movies whose charmingly simple effects made the viewing experience less immersive and, therefore, less terrifying than more contemporary offerings. I was a particular fan of the atomic monster movies (except the ones about insects!!!) and the classic Universal creature features. I wanted to be best friends with Godzilla and I was deeply, unapologetically in love with Boris Karloff because I had visions of costume parties complete with prosthetic make-up dancing in my head. (I was six, okay?) Although I loved the absurdity of the 1950s B-movies, there was something about the Depression-era monster movies that made them favorites. It was only when I was old enough to assimilate abstract concepts like allegory and pathos that I realized that part of the appeal of the 1920s/1930s films was that the stories made the audience question what it really meant to be a monster. (The other part was the outsider’s sense of kinship I felt for the “monsters,” but that’s an entry for another day. Or never. Let’s say never.)

* * *

So what makes a monster?

In some horror movies, the monster is a nonhuman creature that is so grossly anomalous that it is frightening. In others, the monster’s grotesquerie results from a deviation in character or behavior that inspires disgust. For me, the most terrifying monster is the being whose cruelty or wickedness is not immediately evident, regardless of how normalized their behavior is. I’m less scared by things that go bump in the night than by people who can visit suffering on others in the light of day because other people give them cover.

Which brings me to Jaws and the Brooks Brothers Brigade. First things first: Jaws is a horror movie. No, I will not be persuaded otherwise.

As for the Brooks Brothers Brigade, their calculated decision to protect the island’s economy at the expense of human life is monstrous, no matter how normalized it is.

We see this play out time and again in real life. Businesses (and the governments beholden to their interests) downplay and even hide evidence of danger from the public because the truth would hurt the bottom line. Working conditions, public health, environmental safety, food safety—profit will always come first and regular people being injured, maimed, or killed is seen as part of the cost of doing business. This attitude is monstrous.

As the current U.S. administration dismantles regulatory infrastructure and public health institutions, as my tax dollars are stolen away from the few programs designed to prevent social murder to funnel cash directly into the pockets of people who have more money than they could spend in a hundred lifetimes, as I remember my Intro to Bioethics professor’s lecture that “all regulations are written in blood and all social welfare programs were paid for in blood,” I can’t help but think of how Mayor Vaughn was all too happy to strongarm people into going into the water while he stood safely on the shore, until the shark threatened the safety of his own kids. That apathy is monstrous. And even so, I find myself wondering is there a breaking point that will shake these people from their obsession with profit above all else? Then reality kicks in and I remember it is unlikely, because they are monstrous.

In Jaws, the textual monster is a shark—in reality, behind the scenes, it’s a mechanical puppet controlled by several people. But the metatextual monster is similarly puppeteered by people, some with more control, some with less, but all playing a part—because capitalism is nothing without the people who perpetuate the system.

The monster isn’t capitalism itself, but the people driving the system. The monster is everyone who aids and abets those who drive the capitalist system. The monster is everyone who seeks compromise with them.

The monster is people. And in Act One, it’s the people in positions of public trust, like the mayor, coroner, and newspaper editor, who are maintaining the system.