On Frankensteined Architectural Elements As Visual Storytelling in Jurassic Park (1993)

In what will be a surprise to absolutely no one, I’ve been struggling with writing because of chronic illness and ::gestures broadly at the state of the world::. When I’ve been feeling well enough to write, it has felt frivolous to write silly little nonsense about silly little set pieces in silly little movies and tv—to the point that I considered giving up the newsletter altogether. I was very nearly about to pull the plug, until a recent trip that involved a lot of watching movies and tv with someone who also likes to analyze media. Our dialogues reminded me that media criticism fills my cup like few other activities can. It’s such a simple joy to notice silly little details and consider what they mean. And I decided, by Jove, that I’m going to write some silly little nonsense after all, because what the hell are we fighting for if not a world where everyone has the freedom, safety, and means to be frivolous.

So join me in taking a break and recharging. I’ll see you again soon, organizing and protesting and generally reminding the John Hammonds and InGens of the world that our government works for us, the economy will fall to shit without us, and there are more of us than there are of the few in power.

* * * * *

As y’all might know from my liveblog of Jurassic Park (1993), I was a big fan of the visual storytelling in the film. One aspect I especially enjoyed was the architectural design of the visitors’ center. At the risk of summoning The Sometimes The Curtains Are Just Blue Brigade, I’ve been doing a lot of thinking about how the design of the visitors’ center as metatext supports the thesis of the overall film as a text.

Here's my working theory: within the reality of the film, the visitors’ center is intended as a temple to man, as a god of creation. However, because Hammond cares more about appearance than function, some of the architectural elements of the visitors’ center end up subverting the intended design, literally elevating form over substance, to the detriment of the structural integrity of the building. As a result, the visitors’ center becomes a visual shorthand for the park itself, which is fated to be destroyed by Hammond’s vanity and greed.

Throughout the film, we learn that Hammond has selected flora and fauna for the visual impact and the bragging rights, without a solid understanding of their function or significance in the context of their native ecosystems. West Indian lilac. Toxic plants. Velociraptors. A dinosaur that spits an enervating agent that spells certain death. Why? Because fuck you, that's why. Because who was going to stop him? Because he felt like it. Because he could.

He took the same appearance-obsessed approach to the architectural elements of the visitors’ center. Although there are a few design choices that scream visual irony, I’m going to spare us all and today, I will focus on the exterior of the building.

* * * * *

Let’s talk about my architecture bonafides! I don’t have any! So glad we cleared that up.

No really, I just love architecture. A lot. I particularly love classical architecture. I love reading about architecture. I love watching documentaries about architecture. I love going on educational tours led by people with architecture degrees. Let's call it A Very Special Interest™.

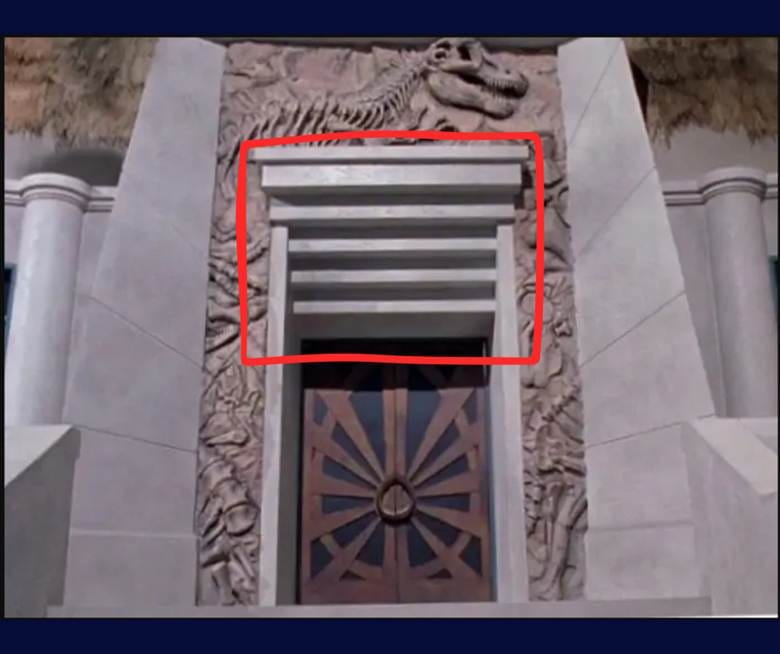

Anyway, here's the exterior of the visitors’ center.

In the early 1990s, post-modernism was at its peak and the style’s influence on the design of the visitors’ center is evident.

What is post-modernism?

As the name suggests, post-modernism is what came, well, after modernism. The trouble, of course, is that modernism is also defined by the artistic and architectural influences that preceded it. So to answer what either of these movements were, we need to compare them to what came before. At the risk of oversimplifying a rich and complex history: in the 19th century, architecture in the West was ornate, heavy with symbolism, and rich in reference to ancient architectural styles of the Mediterranean and various architectural styles from the Eastern Hemisphere.

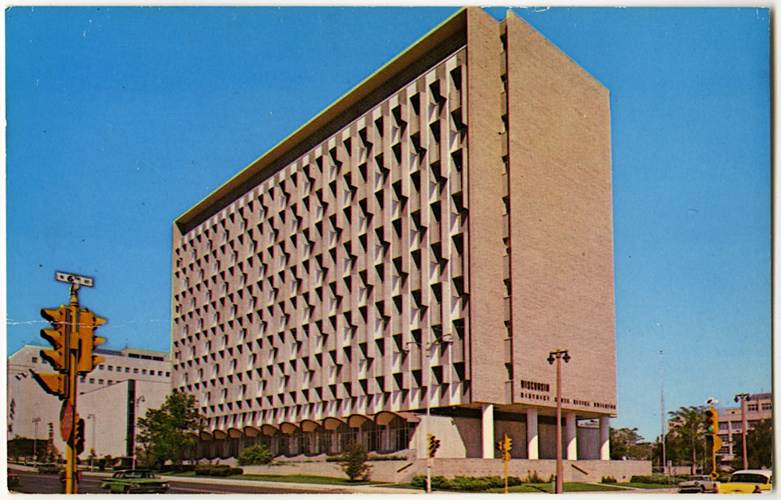

In the early 20th century, a cultural movement emerged that eschewed ornamentation and symbolism, in favor of minimalist, functional aesthetics. That movement was modernism.

In the 1960s, post-modernism reintroduced ornamentation and embraced symbolism, as a reaction to the perceived austerity and uniformity of modern architecture. A hallmark of post-modern architecture is that it combines elements from earlier architectural styles and draws inspiration from classical designs to communicate a civic meaning. Some examples of post-modern architecture are:

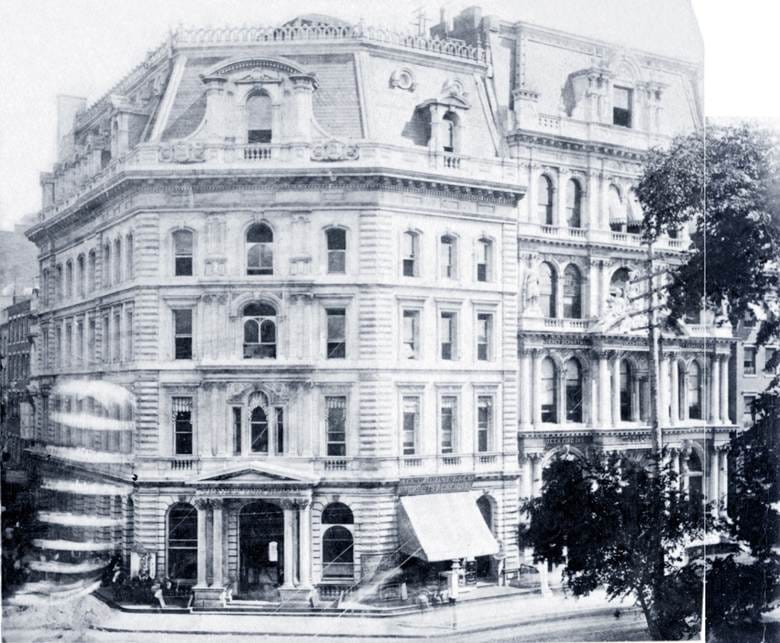

- the AT&T Building, which pays homage to 1920s skyscrapers built for earlier commercial titans;

- Neue Staatsgalerie, a museum dedicated to postmodern art, that blends classical elements like colonnades and rotundas with industrial steel and glass;

- and the Carl B. Stokes U.S. Courthouse, a dressed-stone government building that borrows from the Beaux-Arts designs of other federal buildings around it.

As a contrast to modernism, which focuses solely on functionality, post-modernism integrates symbolism and function.

In the case of the visitors’ center, the same is true. By its function, the visitors’ center is just that—a central location to welcome visitors to the park. But through the symbolism of the architectural details, it communicates Hammond’s vision of Jurassic Park (and foreshadows the downfall of the whole project).

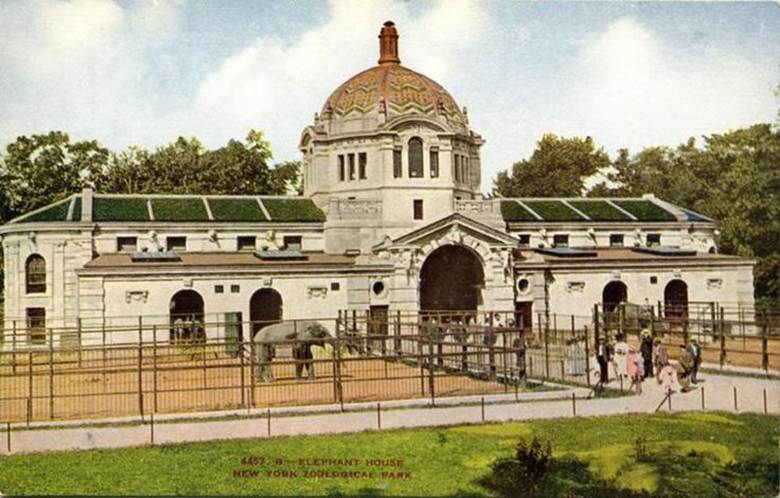

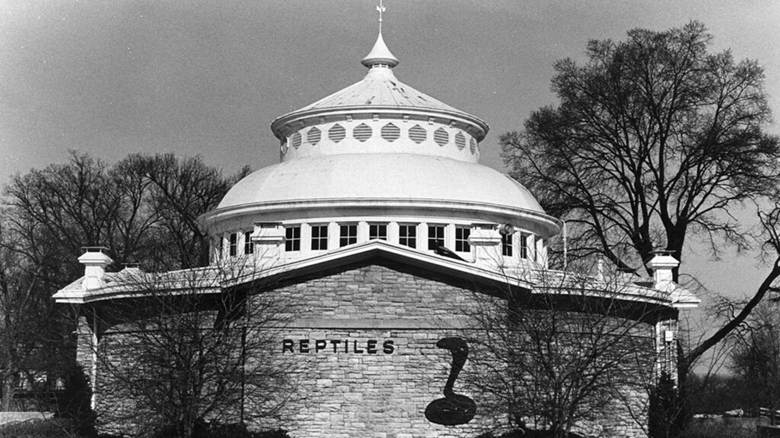

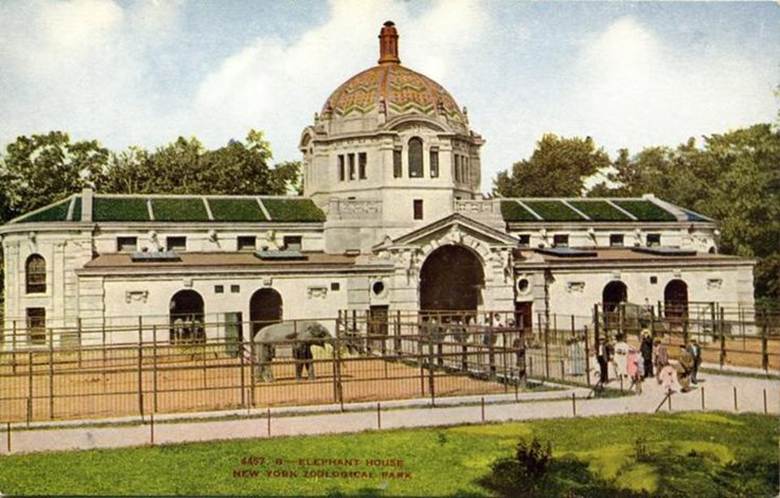

Let’s start with the overall structure, which is reminiscent of Orientalist architecture, a baroque style of building that borrowed heavily from Eastern designs. In the West, Orientalism is common in zoos built in the 19th century, as the design was meant to evoke associations with “exoticism” and conquest—specifically the triumph of supposed “civilization” over “savagery” and taming unruly nature into submission and ultimate captivity. (For more on the dark history of zoos in the West, check out the endnotes.)

This image of conquest fits with Hammond’s overall colonialist vibe—from his impeccably tailored, perfectly starched, unsullied safari suit, to the fact that he owns a “game reserve” (complete with game warden) in a former British colony.

The theme of conquest continues in the details of the entryway to the building.

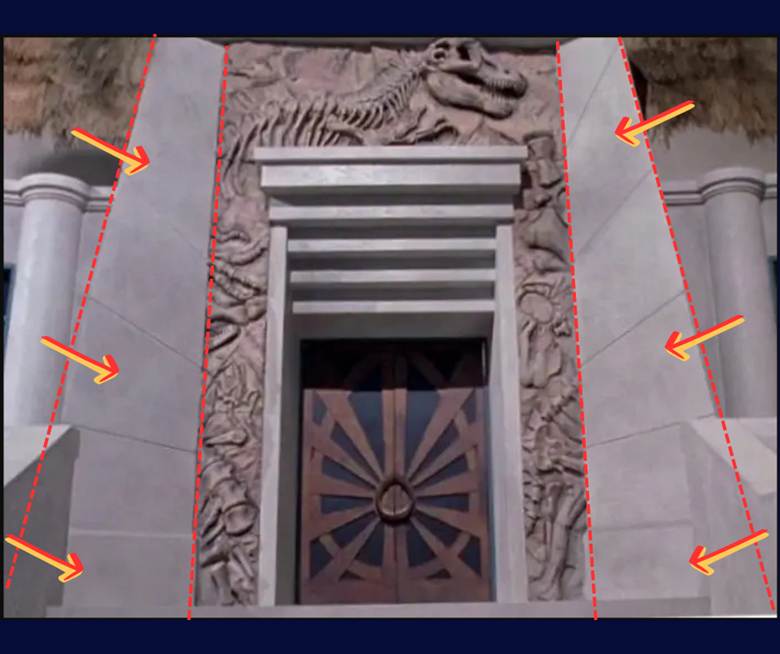

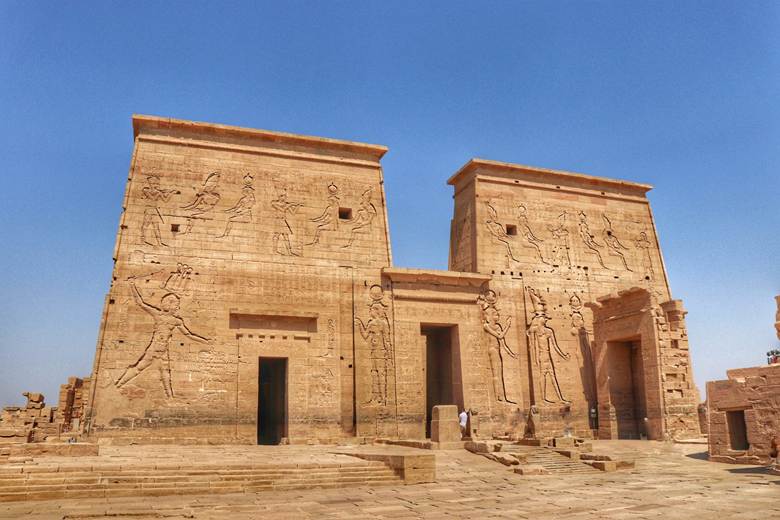

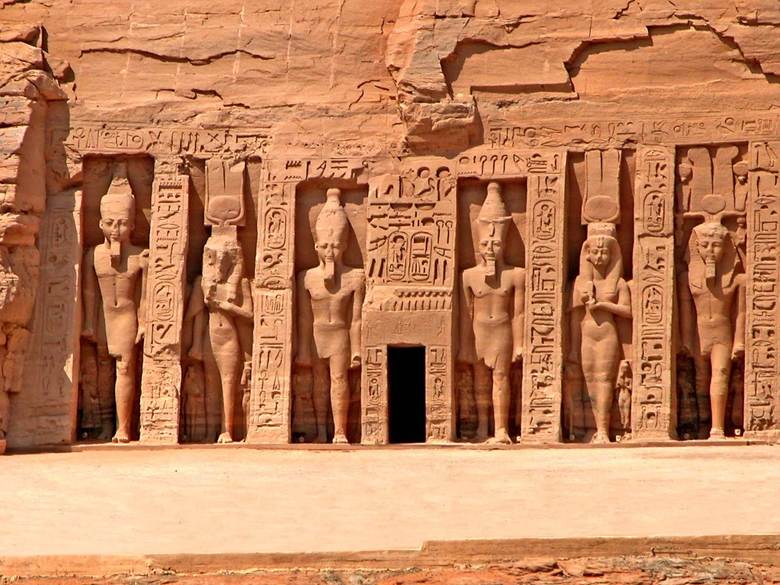

The shape of the buttresses is trapezoidal.

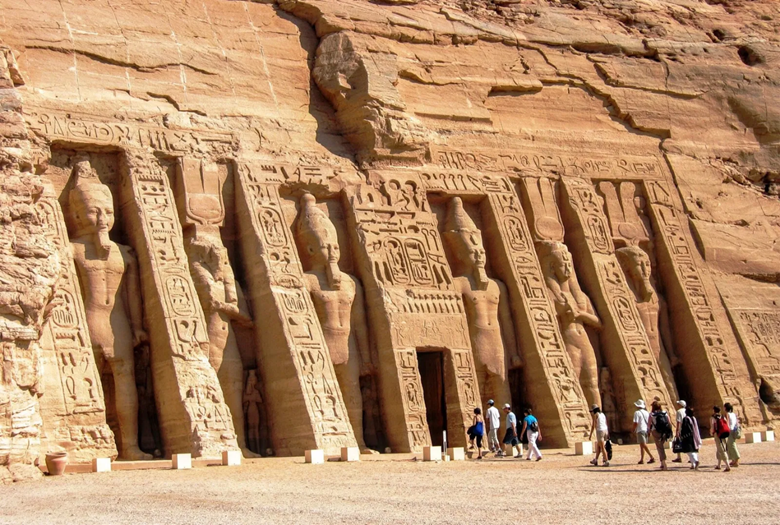

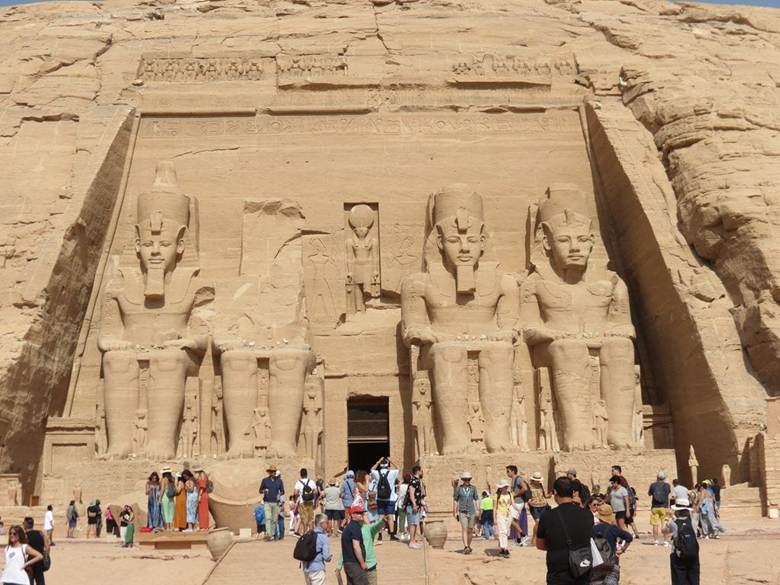

This shape is reminiscent of the entryways of the Nubian monuments from Abu Simbel and Philae—structures built to cement a pharaoh’s legacy and elevate him to godhood, conquering death.

(The irony of Abu Simbel and Philae, of course, is that the structures were ultimately endangered by yet other men playing god, i.e., altering the natural course of the Nile.)

* * * * *

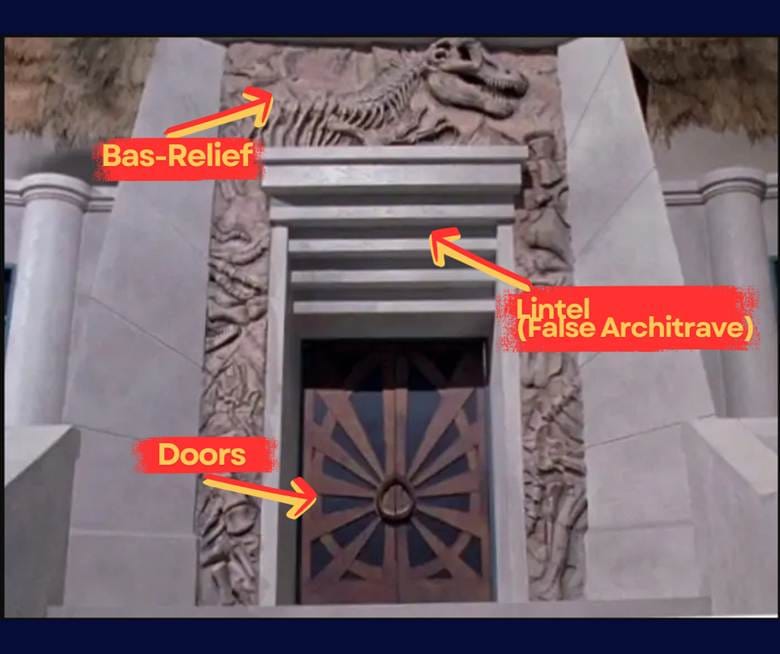

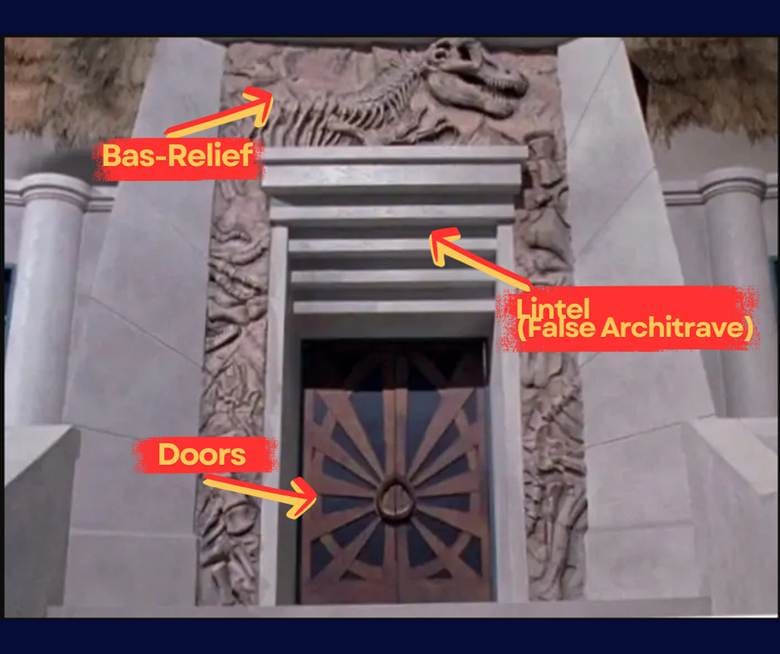

There are additional details consistent with a theme of conquest and dominance. Specifically, three components of the doorway itself are rich with this symbolism: (1) the doors, (2) the lintel (or false architrave), and (3) the bas-relief.

The Doors

Let’s start with the doors, which have an incredible ovate design superimposed on a sunburst.

Eggs are generally representative of creation, while the sunburst, which is commonly associated with a new dawn, has been coopted by several empires as a symbol of glory through—you guessed it—conquest . The minimalist sunburst, which has the rays widening as they get further from the center, is one of the most iconic motifs of the Machine Age and the technological optimism of the era.

Taken as a whole, the wood and glass doors suggest the creation of a new tomorrow through technological innovation. Because opening the doors cracks the egg down the center, there’s a sense that when you walk through the doors, that you’re walking into a cradle of creation.

The design is a masterclass in foreshadowing the egg lab, the dinosaurs reproducing on their own, and how Hammond has so thoroughly bought into his mythology of being a life-giver, that he fails to recognize how his hubris is engineering the destruction of everything he has made.

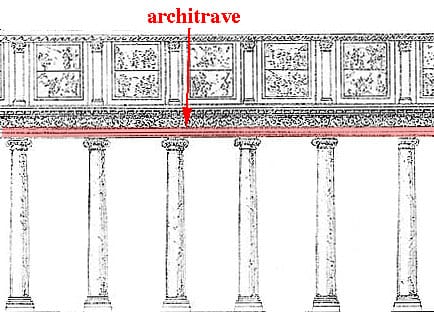

The Lintel (or, More Accurately, False Architrave)

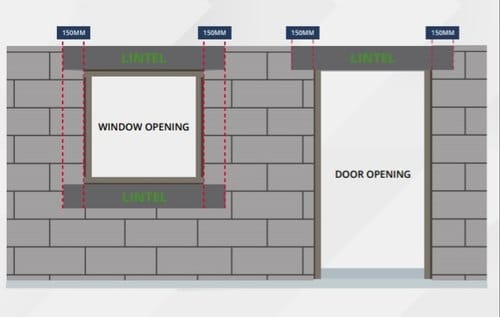

The lintel is next. “What’s a lintel?” you ask. So glad you did. A lintel supports the weight of the structure above an entrance. It’s what keeps the door (or window) from collapsing under the weight of the structure that sits on top of it.

Though some lintels can be ornate, they ultimately serve a functional purpose, so if the design undermines the function, you’ve got yourself a problem.

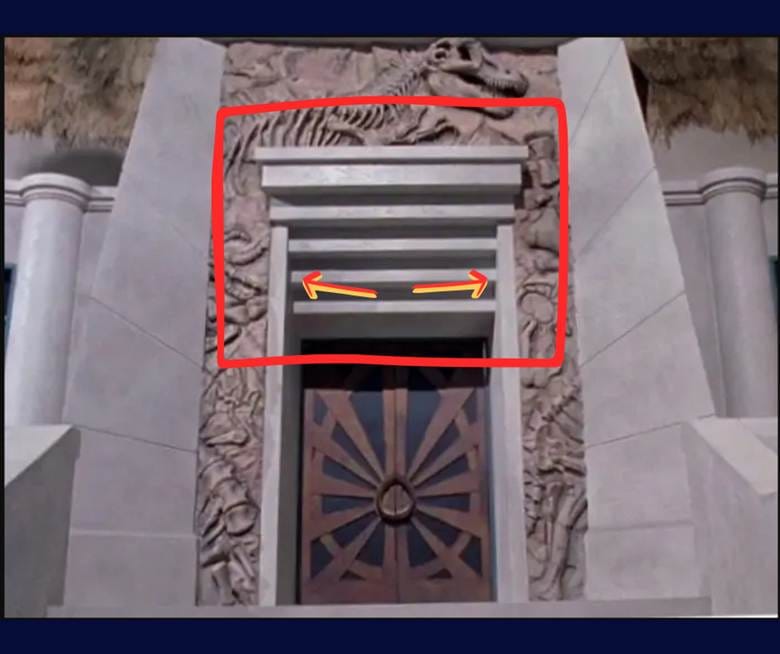

The design of this lintel is fascinating.

Have you ever walked down a set of stairs and the “ceiling” of your stairwell was a perfect negative of the steps you were using such that the “ceiling” and the floor could fit together like puzzle pieces? That’s what’s going on with this lintel, which has a design suggestive of the underside of steps.

From the perspective of a person entering the building, the steps look like they’re descending. Because these are made of concrete, they look almost rock-cut—like the steps in Egyptian tombs, suggesting that one is descending into a holy space. But because the steps have a contemporary, rather than ancient feel, along with the ovate sunburst, the overall effect is of an entrance to a holy space made possible by modern innovation. More conquest.

You thought I was done with the lintel, didn’t you? Sike!

Here’s where the design gets really interesting. Remember that I also called the lintel a “false architrave.” An architrave is to a pair of columns what a lintel is to an opening in a structure. Like a lintel, an architrave is load-bearing and is designed to protect the negative space beneath it.

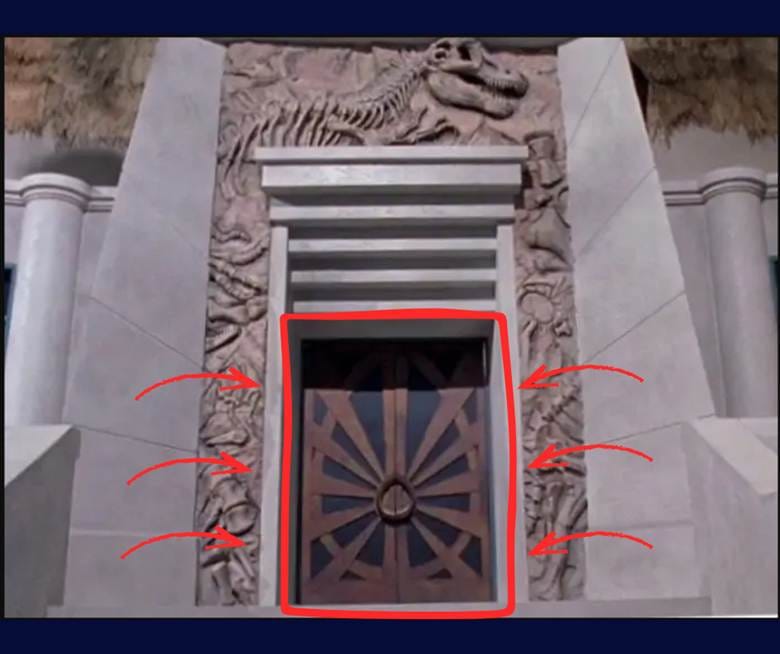

Yet here, the “architrave” isn’t resting on top of columns—it’s coming between these columnar elements, separating them.

Columns are load-bearing structures, people! And this oversized, grandiose, stone lintel/false architrave design is literally destabilizing the columns, to rest immediately on top of the wood and glass doors—two materials that are weaker than the stone sitting above them. Thus, the architrave is not fit for its purpose, which is to protect the elements under it. More on this later!

The Bas-Relief

Here’s the bit that convinced me that the visual metaphor wasn’t all in my head: the bas-relief—the carved stonework between the door and the buttress depicting washed out dinosaur fossils. This design suggests that using archaeology to study once-living things is itself a relic that will be replaced by the new science: resurrecting what nature saw fit to extinguish.

This type of sculpture is rendered similarly to the hieroglyphics and the gods at the entrance of Abu Simbel.

While the design of the bas-relief of the visitor’s center is likely meant to be suggestive of the excavation that revealed the DNA that makes InGen’s life-giving work possible, there’s a visual weight to the placement and size of the bas-relief, such that the fossils are visually overpowering the doorway underneath.

Adding It All Up

Putting all of the symbolism together, the elements—the sunburst egg of creation, the rock-cut steps of discovery, and the fossilized dinosaurs of the past—convey that human innovation can literally bring the past to life, inviting park attendees to revel in man playing god—in conquering nature to give life to the powerful and terrible creatures InGen Dr. Frankensteined into existence from dye-no and frog dee-en-ay. But the elements themselves are stitched together based on the appeal of their form without any care for their cohesive function—or the result. Just like the park itself.

The cradle of creation represented by the doors is rendered in wood and glass—fragile next to (and under) the stone surrounding it. And the doors are threatened by the weight of the bas-relief because the false architrave is failing to bear the weight above it. Innovation is failing to respect the (literal) physical influence of natural history and will be unprepared for the consequences.

The architectural elements are a physical representation of the various ways Hammond put more stock in appearance than safety in building Jurassic Park, and ultimately destroyed his project before it could see the light of day. It’s an incredible visual metaphor for Hammond's fixation on innovation at the expense of everything else. He cared more about creating something impressive than how that creation would impact the people interacting with it. Despite having an unimaginable technological innovation at hand to solve real-world problems, Hammond chose to use the technology to build a theme park that only other wealthy people could afford.

At one point, Hammond defends his choice to build Jurassic Park by insisting that if he were using the technology to bring condors back from the brink of extinction, Malcolm would not object to the Park’s breeding program. But the fact is Hammond didn’t use the technology to save any of the dozens of species threatened by habitat destruction, pollution, and climate change. Instead, he chose to build a theme park populated with fucking dinosaurs and spend a fortune on marketing to convince people they can’t live without it.

Why? Because fuck you, that's why. Because profit demands it.

I can’t help but be reminded of the tech broligarchs who insist on driving the denizens of Earth toward planet-warming extinction to build data centers for the largely useless “AI” they keep trying to cram down our throats. Said “AI” only exists because they sunk trillions of dollars into stealing the intellectual property of actual creators to build a machine to Frankenstein it all together, and now they need someone to sell it to. Why? Because profit, dammit.

I’d say that Jurassic Park was weirdly prophetic of the Move Fast, Break Things era we’re all trying survive right now, except little augury was required. The fundamentally extractive nature of capitalism is as eminently predictable as the atomic clock. Unregulated capitalism was always going to end with us holding onto our butts.

And to that I say:

Down with the capitalocene and its evangelists. ::cue Dino Rex Machina::

Endnotes (No, they're not formatted properly. I draw the line of pedantry at formatting endnotes)

ICTNews.org, "Human Zoo: For Centuries, Indigenous Peoples Were Displayed as Novelties," Aug. 30, 2011; https://ictnews.org/archive/human-zoo-for-centuries-indigenous-peoples-were-displayed-as-novelties/

Mullan, Bob and Marvin Garry, Zoo culture: The book about watching people watch animals. University of Illinois Press, Urbana, Illinois, Second edition, 1998.

Mangubat, L. (2017). The True Story of the Mindanaoan Slave Whose Skin Was Displayed at Oxford. Esquire Publications.

"On A Neglected Aspect Of Western Racism" Archived 16 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine by Kurt Jonassohn, December 2000, Montreal Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies.

Roberto Aguirre, Informal Empire: Mexico And Central America In Victorian Culture, Univ. of Minnesota Press, 2004, ch. 4.

Emery, Tom (28 May 2022). "Quintuplets' story remains one of shame, regret; sisters lives on display for the fortune of others". Journal-Courier.

Abbattista, Guido (2014). Moving bodies, displaying nations : national cultures, race and gender in world expositions: Nineteenth to Twenty-first century. Trieste: EUT. ISBN 978-8883035821. OCLC 898024184.

Zeitler, Annika (3 October 2017). "Human zoos: When people were the exhibits". Deutsche Welle.